Welcome, fellow wanderers, to the boundless universe beneath our feet, above our heads, and often, right under our very noses. As your Resident Entomologist for Wandering Science, I spend my days peering into the minuscule, seeking out the monumental marvels that most of us overlook. It’s a world where the laws of physics are bent, where engineering feats occur on scales invisible to the naked eye, and where life thrives through an astonishing, inherent ingenuity. Forget the grand vistas for a moment; let’s zoom in, truly zoom in, to where the magic of existence is stitched together with unimaginable precision.

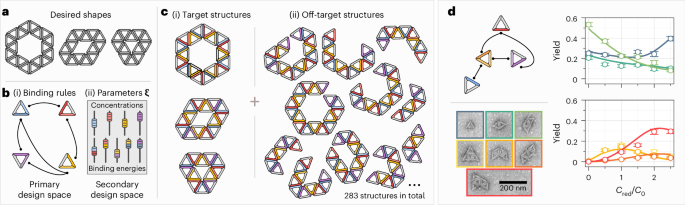

A polyhedral structure controls programmable self-assembly

The Micro Hook: Zooming In

Imagine standing at the edge of a dewy meadow at dawn. The air is cool, and the world is just waking. But instead of the calls of birds or the rustle of larger mammals, let your focus shrink. Now, picture a single strand of spider silk, catching the first rays of sun. It shimmers, almost iridescent, stretching taut between two blades of grass. To our eyes, it’s merely a delicate thread, easily broken. But under a powerful microscope, this “thread” reveals itself as a marvel of biomolecular engineering. It is a protein fiber, yes, but its strength, elasticity, and incredible resilience are not accidental. They are the result of a precise, intricate arrangement of molecules, folded and bonded into specific, repeating patterns. This isn’t just random bundling; it’s a programmed assembly, a blueprint encoded within the spider’s very being, dictating how these minute components come together to form a structure of astounding integrity. This concept, this inherent ability of biological systems to construct complex forms from simple building blocks, is what truly captivates me. It’s the ultimate example of nature’s hidden genius, a ‘programmable self-assembly’ that has been perfected over millions of years of evolution.

The Discovery: Data/Behavior Analysis

It is in understanding these natural processes that we begin to appreciate the profound implications for our own scientific endeavors. Take, for instance, the intricate architecture of a viral capsid – a protective shell that encases genetic material. Many of these capsids exhibit stunning polyhedral symmetry, a geometric perfection that allows them to self-assemble from numerous identical protein subunits. This isn’t a haphazard process; it’s a highly controlled, step-by-step construction dictated by the inherent properties and interactions of the constituent proteins. Researchers, inspired by such natural phenomena, are now developing mathematical frameworks to identify precisely how such complex structures can be assembled from simpler components. They’re looking at the “rules” nature follows, attempting to codify them. In the insect world, we see similar principles at play in the formation of the insect cuticle, the precise layering of chitin and protein that gives an exoskeleton its strength, or the crystalline structures within the ommatidia of a compound eye, each perfectly aligned to capture light. These aren’t just fascinating observations; they are living laboratories demonstrating the power of self-organizing systems. The “polyhedral structure” isn’t merely a theoretical construct; it’s a fundamental motif in the biological world, from the microscopic architecture of a virus to the macroscopic precision of a bee’s honeycomb. And it’s this inherent, almost magical, ability of nature to self-organize into incredibly complex and functional forms that continues to fuel our scientific curiosity.

Ecological Context: The Web of Life

These minuscule feats of programmable self-assembly are not isolated wonders; they are foundational to the intricate web of life. Consider the precise, hexagonal cells of a beehive. Bees don’t consciously calculate the most efficient packing solution; their instinctual behavior, guided by inherent biological programming, leads to the creation of these perfect polyhedra. This structure maximizes storage space, minimizes material usage, and provides incredible structural integrity for honey, pollen, and developing young. Without this self-assembled architecture, the colony could not thrive. Similarly, the strength and elasticity of spider silk, formed through the precise self-assembly of proteins into crystalline and amorphous regions, allows spiders to construct elaborate traps and safely traverse vast distances. This silk, in turn, provides habitat, food, and even medicinal compounds. The very exoskeleton that protects an insect from predators, desiccation, and disease is a marvel of layered, self-assembled chitin and protein, forming a lightweight yet incredibly tough armor. These structures are not just about survival for the individual; they are critical components in ecosystem function. The strength of a beetle’s wing, the intricate filtration system in a mosquito’s mouthparts, the light-gathering efficiency of a butterfly’s scales – all are products of molecular self-assembly that allow these creatures to play their vital roles as pollinators, decomposers, predators, and prey. Disruption at this micro-level can have cascading effects throughout entire ecosystems, reminding us of the delicate balance and profound interconnectedness of all life.

The Field Angle: Where Can a Traveler Go to See This?

So, where can a ‘Wandering Science’ enthusiast witness these wonders of programmable self-assembly? The beautiful truth is, you don’t need a high-tech lab or a remote jungle expedition. The hidden world is everywhere. Start in your own backyard. Grab a magnifying glass, or better yet, an inexpensive portable microscope that attaches to your phone. Look at a dew-kissed spiderweb in the morning – observe its geometry, its strength. Examine the intricate patterns on a beetle’s carapace, or the iridescent scales of a butterfly’s wing. These are not just colors; they are structural colors, formed by precisely arranged nanostructures that refract light in specific ways. If you have access to woodlands, gently turn over a log and observe the myriad detritivores – ants, millipedes, springtails. Their very forms, their hard exoskeletons, are testaments to biological self-assembly. For a deeper dive, visit a natural history museum. Many now feature scanning electron microscope (SEM) images that reveal the breathtaking detail of insect anatomy, showcasing the polyhedral structures and intricate patterns that are invisible to the naked eye. Consider a trip to a tropical rainforest, a biodiversity hotspot where insects reach their most astounding diversity and complexity. Here, you’ll find everything from leaf-mimicking katydids whose bodies are perfectly sculpted to blend in, to elaborate ant nests that are engineering marvels. Even a simple walk through a park, with an attentive eye and a curious mind, can transform into an expedition into the world of natural engineering. The key is to slow down, look closer, and allow yourself to be astonished by the sheer genius of life at its most fundamental level. The small world is waiting, eager to reveal its grandest secrets.

About admin

A curious explorer documenting the intersection of science and travel. Join the journey to discover the hidden stories of our planet.

Leave a Reply