Parkinson’s disease as a somato-cognitive action network disorder

The hand, once steady and precise, now hesitated. It hovered above the teacup, a silent tremor beginning its rhythmic assertion, a subtle rebellion against the will. For countless individuals, this involuntary dance of a limb, this faltering step, or the sudden rigidity of movement, marks the insidious onset of Parkinson’s disease. For decades, our understanding of this enigmatic condition has largely centered on the motor system, a narrative dominated by the tragic loss of dopamine-producing neurons in the substantia nigra, and the subsequent breakdown of communication within the brain’s movement circuits. We pictured a brain where the gears of motion were grinding to a halt, a purely mechanical failure. But what if this picture, while accurate in part, was incomplete? What if the struggle to lift that cup wasn’t just a motor deficit, but a deeper, more pervasive disruption of the very network that blends thought, intention, and action into a seamless whole?

This question has propelled neuroscientists into a new frontier of inquiry, challenging long-held assumptions about the brain’s architecture and the etiology of Parkinson’s. The traditional view, rooted in the observation of debilitating tremors, bradykinesia (slowness of movement), and rigidity, posited that the disease primarily targeted discrete motor regions. Treatments, from L-DOPA to deep-brain stimulation (DBS), have historically aimed at restoring or modulating these motor pathways. However, the lived experience of Parkinson’s patients often tells a broader story, one that includes cognitive decline, mood disturbances, sleep disorders, and a host of other non-motor symptoms that are harder to reconcile with a purely motor-centric model. These symptoms, often as debilitating as the motor ones, have long been considered secondary or parallel pathologies, rather than integral expressions of the disease’s core mechanism.

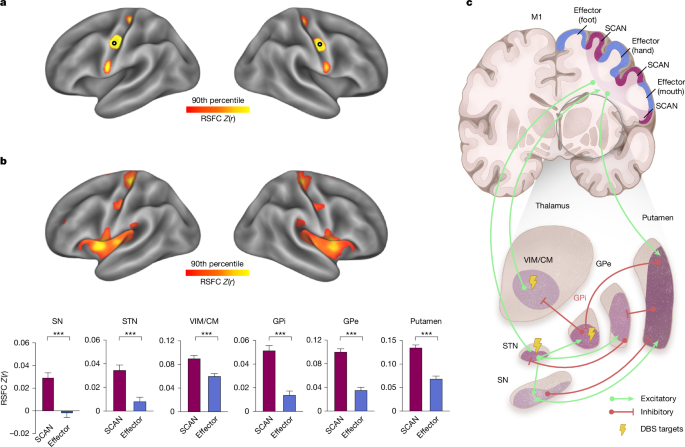

A groundbreaking study published in Nature.com has now offered a compelling re-evaluation, proposing a radical shift in our understanding: Parkinson’s disease may be fundamentally a disorder of the somato-cognitive action network (SCAN). This network, a recently identified and distinct functional system within the brain, represents a fascinating convergence of motor planning, executive function, and higher-order cognitive processing. It’s the brain’s conductor, orchestrating not just the movement itself, but the intention, the context, the decision-making, and the sensory feedback that informs every action we take. The researchers, employing sophisticated functional MRI techniques and detailed anatomical mapping, discovered that the substantia nigra – the very heart of dopamine loss in Parkinson’s – and all established deep-brain stimulation targets are selectively and robustly connected to this SCAN, rather than to the effector-specific motor regions we previously emphasized. This finding suggests that the pathology of Parkinson’s is not just impairing the ability to move, but the very integrated system that allows us to conceive, plan, and execute purposeful actions.

Imagine the brain not as a collection of separate departments, but as a sprawling, interconnected city. For years, we thought Parkinson’s was causing traffic jams on the main motor highway. This new research suggests the problem is much more fundamental: it’s disrupting the central planning commission that coordinates all city services, including traffic, urban development, and public safety. The SCAN acts as this central planning commission, integrating information from various brain regions to ensure that our physical actions are not just mechanically sound, but also contextually appropriate and aligned with our cognitive goals. When this network falters, the tremor is not just a motor glitch; it’s a symptom of a deeper disconnect between intention and execution, between thought and physical reality. This model provides a cohesive framework for understanding why Parkinson’s patients experience not only movement difficulties but also challenges with planning, decision-making, and emotional regulation. These are not separate afflictions, but diverse manifestations of a singular, profound disruption within the SCAN.

This paradigm shift holds immense implications for how we approach Parkinson’s disease, from early diagnosis to therapeutic interventions. If the SCAN is indeed the primary locus of disruption, then current deep-brain stimulation (DBS) strategies, which target specific nuclei like the subthalamic nucleus or globus pallidus interna, may be working precisely because these regions are crucial nodes within the SCAN. This research offers a more precise understanding of *why* DBS is effective and could pave the way for more refined targeting strategies, potentially improving outcomes for both motor and non-motor symptoms. Furthermore, it opens new avenues for pharmacological research, encouraging the development of drugs that not only replenish dopamine but also modulate the broader functional integrity of the SCAN. It also underscores the importance of therapies that integrate physical rehabilitation with cognitive training, recognizing the intertwined nature of somato-cognitive function. The future of Parkinson’s treatment may lie in nurturing this intricate network, rather than solely focusing on isolated motor components.

For the wandering scientist or the curious mind, where can one witness this profound shift in understanding? While the intricate dance of neurons and networks unfolds within the confines of the skull, its echoes reverberate throughout our world. One might begin by visiting the public engagement programs offered by major neuroscience research centers, such as those at the NIH, or leading universities like Stanford or UCL. Many host open lectures, workshops, or even virtual reality simulations that allow a glimpse into the brain’s complex architecture and the cutting-edge research being conducted. These institutions often showcase the very imaging techniques, like fMRI, that reveal the brain’s functional networks in action, bringing the abstract concept of the SCAN to life.

Beyond the laboratory, observe the quiet resilience of individuals living with Parkinson’s. Attend a local support group meeting, or engage with advocacy organizations like the Parkinson’s Foundation or Michael J. Fox Foundation. Here, you’ll find firsthand accounts that beautifully illustrate the struggle to integrate thought and movement, the cognitive effort required for tasks that once felt automatic. Witnessing the careful, deliberate steps, the concentration etched on a face as a person attempts to articulate a thought, or the sheer determination in navigating daily life, offers a profound, human window into the brain’s somato-cognitive challenges. It is in these moments, both in the high-tech scanner and in the everyday human experience, that the true nature of Parkinson’s disease as a disorder of our integrated action network becomes strikingly clear, reminding us that the journey of scientific discovery is a continuous exploration, forever refining our map of the human condition.

About admin

A curious explorer documenting the intersection of science and travel. Join the journey to discover the hidden stories of our planet.

Leave a Reply